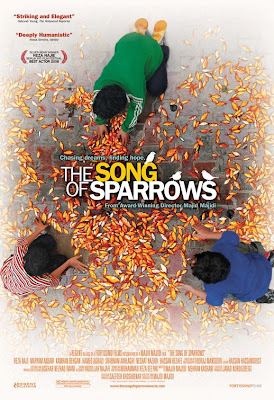

KONANGAL OUTREACH SCREENING

The Song of Sparrows

A film by Majid Majidi

Year : 2008

Country : Iran

Runtime: 96 min

Persian with English subtitles

1st Jan 2010 6 pm

Aruna Thirumana Mandapam

(Next to P&T Quarters bus stop)

N S R Road, Saibaba Colony, Coimbatore.

This screening is supported by

Hollywood DVD Shoppee

N S R Road Saibaba Colony Coimbatore

"The Song of Sparrows" is a fitting name for the new film from Iranian writer-director Majid Majidi. Sparrows are, after all, the most ordinary of birds: small, brown, common. The overlooked and the ordinary is exactly the terrain Majidi loves to walk, and we see again in this film his deep affection for his country's common folk -- with their meager resources, menial jobs and yet surprisingly fulfilled lives.

That is not to say he is content to merely let the camera linger too long or too lovingly, though the cinematography by Tooraj Mansouri is beautiful, from sweeping rural vistas to the choking streets of Tehran and always the faces, etched with grime and life, eyes that pool with hurt, frustration, acceptance..

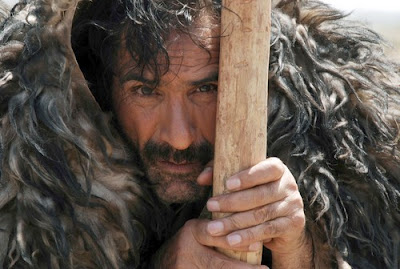

In "The Song of Sparrows," which he co-wrote with Mehran Kashani, Majidi goes down that road again. Here we have Karim (Reza Naji), who works long days on an ostrich farm, caring for the birds and collecting the huge, delicate eggs. But things, which are never easy for this impoverished family man, are about to get more difficult.

Karim’s leathery face makes it difficult to determine his exact age. He could be anywhere from 35 to 55. And it’s highly likely that he’s barely educated, since he’s not so good at making change. Majidi definitely hasn’t created a saint. With bloated pride, Karim doesn’t always do right by his family, violently lashing out when his children infringe on his role as bread winner.

Karim’s leathery face makes it difficult to determine his exact age. He could be anywhere from 35 to 55. And it’s highly likely that he’s barely educated, since he’s not so good at making change. Majidi definitely hasn’t created a saint. With bloated pride, Karim doesn’t always do right by his family, violently lashing out when his children infringe on his role as bread winner.Majidi also enjoys toying with his characters, forever putting them in situations that send their internal moral compasses spinning, letting good and bad choices alike play out long enough for us to see the consequences.

The film abounds in metaphors. Even the son dreams of striking it rich through selling gold—gold fish, that is, and not coincidentally a symbol for prosperity in Iran and elsewhere. But the story is so well told that the symbolism supports rather than sustains the plot. What better metaphor for tenacity than an ornery, ungainly but oddly beautiful ostrich.

The film abounds in metaphors. Even the son dreams of striking it rich through selling gold—gold fish, that is, and not coincidentally a symbol for prosperity in Iran and elsewhere. But the story is so well told that the symbolism supports rather than sustains the plot. What better metaphor for tenacity than an ornery, ungainly but oddly beautiful ostrich.

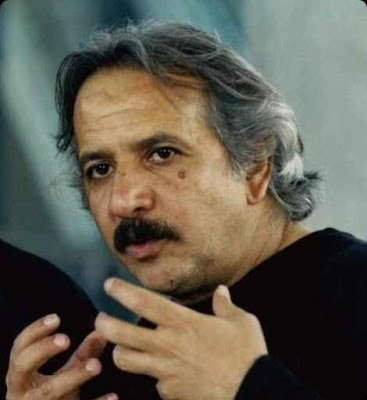

Majid Majidi

Majid Majidi was born in Teheran in 1959 from an Iranian middle class family. He grew up in Teheran and at the age of 14 he started acting in amateur theater groups. He then studied at the Institute of Dramatic Art in Teheran.

Majid Majidi was born in Teheran in 1959 from an Iranian middle class family. He grew up in Teheran and at the age of 14 he started acting in amateur theater groups. He then studied at the Institute of Dramatic Art in Teheran.After the Islamic revolution in 1978, his interest in cinema brought him to act in various films, notably "Boycott" (1985) from Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

His debut as a director and screenwriter is marked by "Baduk" (1992), his first feature film that was presented at the Quinzaine of Cannes and won several awards nationwide. Since then, he has written and directed several films that won worldwide recognitions, notably "Children of Heaven" (1997) that won the "Best Picture" at Montreal International Film Festival and nominated for best foreign film at the Oscar Academy Awards.

His film "The Color of Paradise" (1999) has also won the "Best Picture" award at Montreal International Film Festival. In the USA, it has been selected as one of the best 10 films of year 2000 by Time Magazine and selected by the Critics Picks of the New York Times among the 10 best films of 2000. This film has set a box office record for an Iranian film in the U.S.A. His last film "Baran" has won seven major awards at the Teheran International film Festival in February 2001 and the "Best Picture" award at the 25th Montreal International Film Festival in 2001. After "Baran" he has made five more films till date.

(Source: Internet)